HIGH SCHOOL

Car accident nearly took everything from Ray Pavy — everything but love for basketball

He was supposed to be Jimmy Rayl’s IU running mate. Instead, he became the school’s first wheelchair-using student.

IndyStar

AD

0:30

SKIP

NEW CASTLE – Ray Pavy never got into public speaking. When you grow up as the son of a Baptist minister, it can be intimidating to follow in those footsteps.

“When I evaluate myself to him as a speaker,” Pavy said with a smile, “I come up way short.”

When it comes to basketball, though, there are few more qualified than Pavy to tell a story. Before he starts, there is a moment of silence, maybe two, and a smile. Then a story about Jimmy Rayl, Bob Knight, Bill Garrett, Herschell Turner, Branch McCracken or Oscar Robertson. Or something more current.

Pavy, 76, loves the game. He still attends as many high school games as he can. His favorite player right now is New Castle guard Luke Bumbalough. “He’s one of those kids who finds a way to win,” he said. “Kids like that are not a dime a dozen.”

Sign up!: Don’t miss any Hoosiers news with our new IU Insider newsletter

More:IndyStar basketball book documents the state’s love of the game

Pavy’s mind is a steel trap of basketball knowledge. It has been that way since he grew up in Sullivan in grade school, going to games with Phil Eskew Jr., the son of former Indiana High School Athletic Association commissioner Phil Eskew.

“Everybody has a talent someplace, I guess,” Pavy said. “I can go to a basketball game and see what is happening. I can see how to stop it. I may not be able to stop Bill Russell but for some reason I could see it since I was about 4 years old. Basketball is a fun game because it’s a matchup of minds. There are so many different ways to play, but it is really matching minds provided you can get players to do what you want them to do. It’s fun.”

The joy of sitting courtside and watching a great player — from Bobby “Slick” Leonard at Terre Haute Gerstmeyer in 1950 to New Castle’s Mason Gillis today — has never left Pavy. But there are other things he has missed for almost 57 years. Like that burning in his lungs and the wind in his face during a long run. That feeling when he was tired, physically spent.

Get the IU Insider newsletter in your inbox.

The latest Indiana Hoosiers news from IndyStar IU Insider Zach Osterman. Covering all things crimson on the court.

Delivery: Sun-FriYour Email

Pavy has not had that feeling since Sept. 2, 1961, the day everything changed. He would have been a junior guard at Indiana, probably starting alongside Rayl, “The Splendid Splinter” from Kokomo. A man who is forever intertwined with Pavy.

Instead, Pavy never played basketball again. A moment of silence, maybe two, passes when he is asked about that date.

“I don’t go back and remember any of it,” Pavy said. “Maybe for a lot of reasons.”

***

For Ray Pavy, there was life before the accident and life after the accident.

Pavy grew up in Sullivan, where his father, Raymond Pavy, was pastor of the First Baptist Church. The elder Pavy had grown up in Ripley County and played basketball at New Marion, where his teams practiced outdoors in the late 1920s.

“After they burned the coal, they would get what was left and spread it around for the outline of the outdoor court,” Pavy said.

Sullivan was a great place to grow up, Pavy said, but also remembers it “very much of a football school.” He played on the junior varsity basketball team as a freshman.

“I’m not sure why they didn’t move me up, to be honest,” Pavy said. “They weren’t winning and the ‘B’ team beat the varsity regularly. Most of the kids older than me were more football oriented than basketball.”

Still, Pavy was disappointed when his father transferred to the First Baptist Church in New Castle in 1956. He liked Sullivan. And New Castle, despite its reputation as a basketball mecca, had struggled so much in two seasons that Marvin Wood — who had led Milan to the 1954 state championship — decided to resign after a last-place finish in the North Central Conference and take the job at North Central, which was opening in 1956.

It did not take Pavy long to see that New Castle was perfect for him, basketball and otherwise.

“You couldn’t write a script about a better place,” he said. “They had a senior class of really bright, smart kids. They just needed a shooter. That was like putting a kid in a candy store.”

A sprained ankle by one of the projected starters put Pavy into the starting lineup for his first game as a sophomore, at Greenfield.

“(Buddy) Fisher tipped the ball to me and I went down the court, right into the wall,” Pavy said. “An auspicious start. A turnover, right into the wall.”

It got better from there. Pavy was second-team all-conference as a sophomore and New Castle improved to 14-7 and made it to the regional final before falling to power Muncie Central. As a junior, New Castle was upset in the sectional by Knightstown. While Kokomo’s Rayl set a new North Central Conference scoring record in 1958, Pavy was honorable mention all-conference.

But it was his senior year when Pavy became a well-known name to high school basketball fans statewide. IndyStar’s Bob Collins wrote in early February of 1959: “This is just one man’s opinion, but if somebody should ask me to name the best all-round player in the state I would be tempted to place Ray Pavy of New Castle near the top … he reminds me of (former Tech star) Joe Sexson … an instinctive ability to put the ball in the right place, sneaky speed and a nonchalant, lazy-looking deceptiveness.”

As it happened, Pavy and Rayl met in the final game of the regular season in New Castle’s Church Street Gym. The Kokomo star led the conference scoring race by 10 points over Pavy going into the night. The Church Street Gym predated the current New Castle Fieldhouse, which opened in 1960 and is famously known as the “world’s largest and finest high school fieldhouse” with more than 9,000 capacity.

The Church Street Gym, built in 1924, seated about 1,800 fans. It was cozy and loud. Pavy loved it. “When you think of the top three shooting gyms, there was New Castle, Rushville and Indianapolis Tech,” he said. “The background was just right. They had those long nets. It was a great place to play basketball.”

Pavy and Rayl scorched the nets on that Feb. 20 night. Rayl scored his 49 points mostly from long range, firing from all angles. Pavy drove and shot his way to 51 points. Rayl took home the conference scoring championship. Pavy and New Castle took a 92-81 victory. “The Church Street Shootout,” as it became known, became one of those forever immortal Hoosier basketball classics.

Doyel: Jimmy Rayl’s life after basketball started young

“I don’t know what other people would think the best five Indiana high school games historically would be,” Pavy said. “But that one would probably be one of the five.”

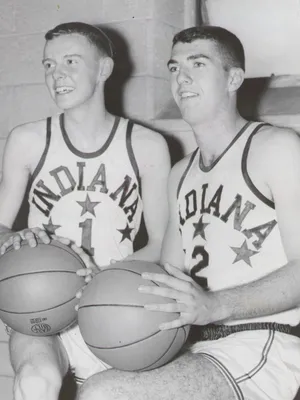

Rayl wore No. 1 that June for the Indiana All-Stars after winning IndyStar Mr. Basketball and leading Kokomo to the state championship game. Pavy wore the No. 2 jersey after averaging more than 23 points per game as a senior and setting the school’s all-time scoring record.

A few months later, they would be teammates at Indiana. Rayl was on his way to becoming a college All-American. Pavy’s journey would take a turn.

College basketball recruiting in 1959 hardly resembles what it is today. Indiana players filled the rosters of Southern schools in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. Pavy remembers coaches from Houston, Tulane and Vanderbilt coming to New Castle after his senior season.

“I just hoped I could get a scholarship and go to college,” Pavy said. “I really didn’t know much about it.”

Branch McCracken was nearing the end of a legendary 24-year run at Indiana that included two national championships. McCracken contacted Danny Danielson, a New Castle businessman who was on the IU board of trustees to inquire about the star senior. Pavy visited the Bloomington campus with his parents.

“Branch was a mammoth man,” Pavy said. “Everywhere he walked, he cast a big shadow.”

It was not a hard sell to get Pavy to come to IU. He had grown up watching Bill Garrett, Slick Leonard and Dick Farley, all former Indiana high school stars, play for the Hoosiers. He had been in the bleachers when Farley led tiny Winslow to the 1950 regional championship at Adams Coliseum in Vincennes.

When Pavy arrived in Bloomington, he roomed with former Shelbyville star Gary Long in a Sigma Nu fraternity house. “He could concentrate better than anybody I have met in my life,” Pavy said of Long. “You could have shot a gun off when he was studying and he wouldn’t hear it.”

Freshmen were not eligible to play college basketball in those days, which meant Pavy, Rayl and Fort Wayne South star Tom Bolyard were among those relegated to intrasquad games played prior to the varsity. “A long year,” Pavy said. But it was a productive year. He watched as big Walt Bellamy and rugged Frank Radovich led the Hoosiers to a 20-4 record and second-place finish in the Big Ten behind NCAA champion Ohio State.

The next year, the 6-11 Bellamy’s senior year, Indiana was again an interior-dominated team. Bolyard stepped right into Radovich’s shoes and 6-6 Charlie Hall handled the other forward spot. Long, a senior and Morristown’s Jerry Bass, a junior, saw most of the minutes at guard.

“What I figured out was that if you have an All-American center, you don’t need a person to shoot,” Pavy said. “You need a person to pass. You can play if you pass. How do you get the ball to Bellamy or Charlie Hall or Bolyard? They needed the ball.”

Pavy, after hardly playing at the beginning of the season, worked his way into the starting lineup by February. Though his statistics — in 18 games he averaged 2.5 points — were not outstanding, Pavy’s all-round game and leadership had earned him McCracken’s trust. Indiana won its final three games to finish 15-9.

With the graduation of Bellamy, Indiana figured to be a more guard-oriented team the following year. Rayl, who averaged four points a game as a sophomore reserve, and Pavy figured heavily into that equation. Rayl was the shooter. Pavy was the all-round guard who could do a little of everything.

“The next two years, they needed a shooter,” Pavy said. “Jim could light it up. He could beat you today. All the Purdue people talk about (Rick) Mount. He’s not as good as Rayl. Jim could shoot as well from 35 feet as 10. A skinny little kid, maybe 135 pounds, but he had great strength out of his legs.”

Rayl would average 27.5 points per game over the next two seasons. From a front-row seat, Pavy would marvel at his former high school rival’s shooting touch.

***

Labor Day weekend, 1961. Pavy, 19, was driving on a rain-soaked patch of U.S. Highway 52 a few miles northwest of Fowler in Benton County. His fiancé, Betty Sue Pierce, was riding with him en route to a wedding of one of Pavy’s fraternity brothers in Whiting. Pavy’s sister, Betty Walker and her three kids — Billy, 9; Paul Ray, 7 and Janice, 5 — were also hitching a ride to meet her husband, William, in Hammond, and then back to their home in Waukegan, Ill., where he was stationed at Great Lakes Naval Base.

On a curve in the highway, at 10:35 a.m. on Sept. 2, 1961, Pavy’s car crashed into an oncoming truck carrying race horses. Pierce, his fiancé for nine months and a New Castle girl, died three hours later.

“We hadn’t set a date yet,” Pavy said. “Probably a year or two down the road.”

Pavy’s oldest nephew, Billy, suffered severe injuries to his head and was initially listed in critical condition. His sister and her other two children escaped serious injury. After surgery, Billy fully recovered and never suffered any lasting effects of the injury.

The accident left Pavy paralyzed.

“When a doctor looks down on you and says, ‘You are never going to walk again’, that is a tough medicine to take,” Pavy said.

For most of the next three months, Pavy underwent multiple surgeries on his back and physical therapy at Long Hospital in Indianapolis. He had his share of visitors, including then-Indianapolis News sportswriter Ray Marquette.

“Ray would call and say, ‘Do you think I could sneak you out and go see Purdue play?’” Pavy said of Marquette, who was killed in a plane crash in 1978. “So he did. And then he’d sneak me back into the hospital.”

Despite the prognosis, Pavy remained resolute that he would walk again. His doctor, Bill Freeman, talked often about living a “normal life.” In the months after the injury, that meant getting back to school, then back to basketball. Over time, “normal” began to mean something different.

“Times were different then,” Pavy explained. “Now, anybody who plays wants to be an NBA star. That wasn’t one of my goals. I wanted to coach. So I was trying to figure out, ‘How do I gain knowledge? Will they ever let somebody in a wheelchair coach? That became the driving force.’”

Where are they now?:Years after basketball, John Kinman still recognized in Madison

More:IndyStar basketball book documents the state’s love of the game

Pavy was out of school for a full year, working for several months at the New Castle-based Modernfold company. When he returned to Bloomington, Pavy joked: “I was the handicapped student.”

He made it work. In the mid-1960s there was no such thing as handicapped-friendly facilities. But Herman B Wells, who was the IU president until 1962 before becoming the chancellor, helped make it possible for Pavy to attend the classes he needed. His classes were either on the first floor of buildings or with access to a freight elevator for his wheelchair.

With the help of his fraternity brothers and professors, Pavy was able to get everywhere he needed to be and graduated in 1965. He is believed to be IU’s first wheelchair-using student.

Pavy was on track to his dream of coaching. But there were also daily reminders about how much had changed since that rainy September morning in 1961.

“Why me?” Pavy said. “I say that every day. It takes a long time to get over that. It changes your whole life, totally. Simple things like getting from point ‘A’ to point ‘B.’ Maybe you can’t get there. You have to rethink the whole process in your mind and plan differently. It also doesn’t take you long to get mad at the person who parks you in so you can’t get back in your van.”

***

Pavy did coach. In 1966, he was hired at Sulphur Springs. The Henry County school was in its last year before consolidation and had not won a game the previous season. The gym floor was 35 feet wide and 60 feet long.

“I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” Pavy said.

Looking back, he said it was maybe the best year of his life. Sulphur Springs went 12-8 and even won a sectional game for just the fourth time in 17 years.

“I really didn’t even interview for it,” he said. “One of the board members I’d worked with at Modernfold, he said, ‘Why in the world would you want this job?’ I don’t think anybody else even applied for it.”

For Pavy, this was the dream. After his success at Sulphur Springs, he was hired as the coach at Shenandoah, a consolidation of Sulphur Springs, Cadiz and Middletown. Pavy coached there for six years, winning two sectionals and compiling a 90-43 record.

“I got fired,” he said. “We had won 19 games that season. How are you going to fire a guy who did that? Well, they did. We were going to be good the next two years, but that was it for me.”

Doyel:9 months to live, then 24 hours. But Kevin Massey is still steamrolling obstacles.

At age 31, Pavy was done as a head coach. He had built a house in New Castle in 1972, where he still lives, and took a job in 1973 to teach handicapped children at the school and work as an assistant coach. Pavy met his wife, Karen, when he started teaching at New Castle. They married in April of 1976, at the same time Pavy was finishing his doctorate at Ball State.

“We had 20 people in our doctorate program and 10 got divorces that year,” he said. “I was the only one getting married.”

Pavy spent the next 31 years in a role he came to love — assistant superintendent at New Castle. In that position, one of the duties he took the most pride in was hiring teachers.

“If you can get teachers who are good teachers to help get kids on the right path, then you have really done something,” he said. “We hired some teachers here at that time who were just dynamite. My kids would come home from college and say, ‘That Mrs. Carmony really got me ready for college.’ I’d say, ‘Here’s the keys, go down to school and tell her.’ The pay isn’t great, but the satisfaction is wonderful if you tell them they made a difference in your life.”

The Pavys survived another serious scare in 2011 when Karen, sitting in the second row at the Sugarland concert at the Indiana State Fair, was badly injured when the stage collapsed, a catastrophe that killed seven people. Her collarbone was crushed and her knee was busted.

“We were really fortunate,” Pavy said. “She could have died. When you saw what happened, the fact that she lived is amazing.”

The injury did produce a few light-hearted moments. For about three weeks, both Pavys were in a wheelchair. “We were in different bedrooms for a while,” Pavy said. “So we’d call each other on the cellphone to say goodnight. She doesn’t get near as mad at me when I run into things as she did before.”

The dream changed, but maybe this was the dream after all. Pavy and his wife raised two children and have poured a lot back into New Castle for 45 years. The accident will never be far from mind for Pavy, not as long as he is in a wheelchair. But all of the other things since — the friendships, the basketball games, the teachers hired, the scholarships awarded through the community foundation, his role as treasurer for the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame — those are the things that add up to a great story.

During homecoming week last year, Pavy returned to Bloomington and was honored as a recipient of IU’s distinguished alumni service award.

“I’ve been pretty lucky when you think about it,” Pavy said. “I got a chance to teach. I got a chance to coach. I had the opportunity to do some things in my hometown. I have a great house, a happy marriage. Hopefully our kids were raised the right way. I’ve been in this town long enough that I have some influence to help get things done. It’s fun when you can do what you want to do and see something out there and say, ‘I can go do it.’ I have got to do a lot of things in my life that takes the ‘Why me?’ away.”

Call Star reporter Kyle Neddenriep at (317) 444-6644.