Alfordsville, Indiana, is a town of 112 people today, tucked in the southern swath of the state east of Interstate 69, west of U.S. 231, and far away enough from either to enjoy much economic development.

But this place is not insignificant. It is in the middle of a region that has lived and breathed high school basketball for decades. Thousands of basketball players and coaches have roots and connections to southwestern Indiana. Larry Bird grew up in nearby French Lick.

Bob Knight was slinging chairs just down the road in Bloomington. Before becoming an All-American, Calbert Cheaney was starring in Evansville.

John Wooden led Martinsville to a state championship before becoming a college basketball coaching legend. Jack Butcher, Junior Gee, Damon Bailey and the Zeller brothers have all lived with the passion of basketball in Southern Indiana.

The list is made up of famous players and coaches, national champions and Olympic gold medalists, many of whom played in the NBA.

Clifford “Butch” Canary isn’t on the list. Playing for Alfordsville High School in the late 1950s, Canary never won any state basketball awards or state championships. There aren’t any old statues with his likeness or any old gyms with his jersey hanging from the rafters.

At 16, Butch lost his life to electrocution in front of his father and a few friends and teammates. But the memories that may come around every basketball season draw to focus a Southern Indiana kid whose future in the game was as wide open as it was for all the greats.

I grew up hearing stories about Butch and his skills as a basketball player. Those stories were ingrained in my mind at an early age. I had always wondered about him, about what he might have accomplished. Could Butch Canary have been on the level of Bailey? Is it fair to ask if anyone could be another Bird?

‘Coach Hudson’

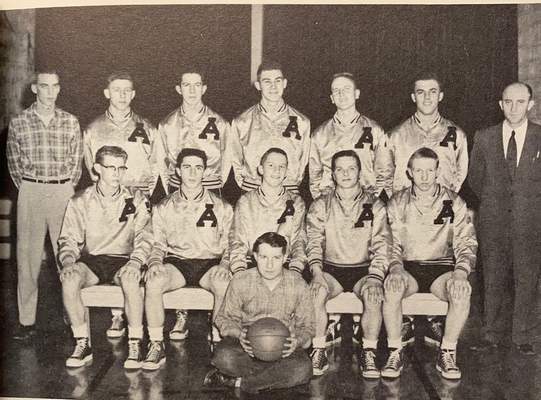

Though tiny today, back in 1957, Alfordsville was bustling enough to have a high school with about 85 students, a couple of stores and a gas station.

Wilbert “Wig” Canary, Butch’s father, coached his son his freshman year at Alfordsville High, but Wig stepped aside after that season to become the school’s principal. Now, he needed a basketball coach.

My dad, Kenneth Hudson, was 23 at the time, starting his teaching career in Alfordsville on 21/2years of college at Indiana University and two years in the Army with a tour of Korea. Soon, Wig Canary named him head coach.

My uncles, Dave Brown and Eugene Schnarr, grew up playing basketball with Butch, and they also played for my dad during his first season at Alfordsville.

My dad, Dave, and Eugene ended up marrying sisters. My aunts have told me how they were not always happy to see “Coach Hudson” come to the house and pick up my mom for dates. They were not fond of their sister dating one of their teachers.

Given the time stamp and the small-knit farming community this all happened in, maybe this could have been a story likened to the movie “Hoosiers.”

But nobody died in “Hoosiers.”

Taken too soon

To write about a player who played 64 years ago revives some old memories – just not the ones you want to think about. As I was researching Butch’s basketball career, I discovered Jerry Osmon, my high school coach, played against him.

When I first asked Osmon about Butch, he had forgotten about his talent or any instances on the court.

But Osmon remembers his death.

The front-page headline from the Washington Daily Times read “Alfordsville Boy Killed Instantly by Electrocution.”

The article describes how Butch, who was working a construction job alongside his dad, lost his footing and fell against a high-tension service line. He grabbed the line with both hands and fell against a metal fence, which formed a mighty ground for the ravaging electricity.

The Washington Daily Times article began with, “A 16-year-old outstanding Alfordsville High School basketball player was shocked fatally yesterday afternoon. Young Canary was a well-known and well-liked boy and was a star basketball player on the Alfordsville High School Team.”

The paper didn’t mention that two of his teammates were also working with Butch and his father or how they witnessed the horrific death. My uncle Dave remembers being at the 4-H fairgrounds and hearing about Butch’s accident announced over the local radio.

Dick Lemon, a close friend and teammate, recalled that Butch’s girlfriend had called the local radio station that morning requesting a song to be played for Butch that afternoon.

She later had to call the station and ask that it not be played.

That school year, my dad moved in with the Canary family and saw a father haunted by loss who grieved for months.

At school, he would sit with my dad at lunch and talk about Butch. When he’d get home from basketball practice or late-night games, Wig would often repeat the same stories about Butch.

Two years after Butch’s death, Wig Canary took another job in the northern part of the state, and the family left Alfordsville.

Might have been

On the court, my dad always believed Butch was on par with talent to Junior Gee, a local star for rival Loogootee. Both were excellent ball handlers and outstanding shooters.

Gee graduated from Loogootee in 1963 and played for legendary coach Jack Butcher, a graduate of Loogootee who played at Memphis State. After college, Butcher turned down an offer from the Boston Celtics to return to Loogootee and begin a legendary high school coaching career.

Gee had a great career, too. He was selected to the Indiana All-Star team and started for three years at the University of Miami, sharing the court with Hall of Famer Rick Barry.

If Butch was as good as Gee, maybe he could have had a Division I college career. Of course, we’ll never know, but Butch did a lot in two years.

Going through archives of local newspapers, as well as my dad’s old clippings, I found out Butch was certainly a standout on his team. In the 13 games I found stats for during his freshman year, Butch averaged 11.2 points with a high of 24. In 18 games from his sophomore year, Butch averaged 17.9 points. He scored more than 20 points seven times.

Regardless of the era, these stats would be impressive for anyone in their first two years of high school. And the stat line could have been better, my dad admits. He owns up to many mistakes he made during his first year of coaching.

“My best player would be the first one out of the game,” he lamented. “I would have coached him a lot differently today.”

Only memories

The footprints of Butch Canary have all but been erased.

Alfordsville High was consolidated into nearby Barr-Reeve in 1965. Eight students were in the last graduating class. The old gymnasium stood in disrepair for decades before it was razed a few years ago.

My dad became a principal himself and, although he retired in 1993, he is still always up for talking basketball.

But he also has memories about Butch that don’t involve basketball at all. Dad trustingly let Butch use his new 1956 Pontiac to take players home after practice. Butch already had a solid work ethic and strong leadership traits. There is no doubt my dad believes Butch’s true accomplishments in life would be far greater than his ones on the court.

Of course, none of those accomplishments were reached. But in Clifford “Butch” Canary’s short 16 years, it is clear he had an impact on the game of basketball and many who knew him.

Epilogue

I am not a journalist. This effort has taken months. My family and parents read the rough draft. My oldest daughter asked, “Why did you write this story?”

Maybe the better question is what was it like to write this story?

Unexpectedly, my dad and I bonded in a way that we had not done in years. It was kind of like shooting hoops in the backyard so long ago, sharing each other’s company and the game we love. Writing the account enabled me to see my dad as a young man, a coach, and view him in a way I had not often thought about.

When I called him and asked him what he thought about the story, he said he cried.

I think I have only seen my dad cry twice in my life. His approval gave me much satisfaction.

For those of us who still have our fathers in our lives, do we ever really stop trying to please them? When we take a step back and look, isn’t that what Butch Canary was trying to do the day he died? He was a son wanting to please his father.

And, to answer my daughter’s question, maybe that is enough of a reason for writing this.