Call it destiny. Call it fate.

Some individuals are brought together to accomplish feats that not only change their times, but also impact the narrative for decades to come.

Two men came together in 1925 in the southern Indiana town of Washington, and their contributions to the game of basketball and race relations should be celebrated by all.

Regrettably, while history may remember their names, their noble efforts in breaking down racial barriers have seemed to be forgotten.

Robert David DeJernett and Burl Friddle were forged together to impact their culture and Indiana High School basketball. Their combined accomplishments need to be known.

Intersecting in Southern Indiana

The DeJernett family ended up in Washington, Indiana, around 1914, two years after Dave was born. John DeJernett, Dave’s father, worked for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and moved his family from Kentucky to Washington. They settled in the west end of town, made up mostly of blue-collar workers and poorer families in the community.

When Dave was eleven, a new grade school opened up close to his house – for whites only.

Before he was old enough to be in high school, Dave was already working on a farm and delivering ice and coal to homes in the area to help provide for his family. At the same time, he was falling in love with the game of basketball.

He played in backyards and on school grounds – a practice common for many young Hoosiers growing up in Indiana. He was an average student in school, as school work had a tendency to interfere with basketball.

—

Burl Friddle had already made quite a mark on the game of basketball before he reached Washington. He was a member of the “The Franklin Wonder Five” that won three Indiana state titles from 1920-22. The same five players then went on to Franklin College and were undefeated National Collegiate Champions in 1923, beating Purdue, Notre Dame, Illinois, and Wisconsin in the process.

After playing a year of pro ball after graduating, Burl started his first year as head coach at Washington High School in 1925. He soon discovered “Big Dave” playing on the school playground. Visions of grandeur followed.

Friddle envisioned Dave controlling center tip-offs and becoming an integral player in his program when he reached high school. The advantage would be staggering, as center jump balls happened after each made basket (the rule was changed in 1937).

Winning center jumps led to winning basketball games.

The Indiana Klan

The black population in Indiana doubled from 1910 to 1930. During the same period, the Ku Klux Klan saw unprecedented power in Indiana. By 1922, two thousand Indiana residents were joining the Klan weekly. That same year, the General Assembly of Indiana passed a bill creating “Klan Day” at the State Fair.

D.C. Stephenson, a failed candidate for a Democratic state congress nomination in 1922, became the Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan the next year. His conviction for the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer in 1925 was a blow to Klan membership. As the story was published in newspapers across America, Klan membership plummeted nationally. In Indiana, membership fell from 500,000 that year to 4,000 in 1928.

Although the Klan in Indiana was largely dismantled, its’ ideologies had a firm hold on many citizens. In 1930, the same year Friddle and DeJernett would celebrate their state championship, two young black men were hanged by a violent mob on the courthouse lawn in Marion. The men were charged with murdering a man and raping a woman. Both were being held for trial.

Race relations had been a stain on the reputation of Indiana for many years. At this time, many viewed the state as widely segregated and hostile to change. If there was a catalyst to make positive strives in desegregation and civil rights, leave it to high school basketball. Friddle and Big Dave were ready and willing.

Basketball in Indiana

Indiana was viewed as basketball’s Mecca.

Consider the words of the accepted father of the game, Dr. James Naismith, after he attended the Indiana State Finals in 1925 along with a crowd of 15,000 fans:

“While the game was invented in Massachusetts, basketball really had its origin in Indiana, which remains the center of the sport.”

That same year Washington High School built the first “Hatchet House” with a seating capacity of 5200. Opening night, Washington hosted Martinsville led by their star player John Wooden. Yes, that John Wooden of UCLA fame.

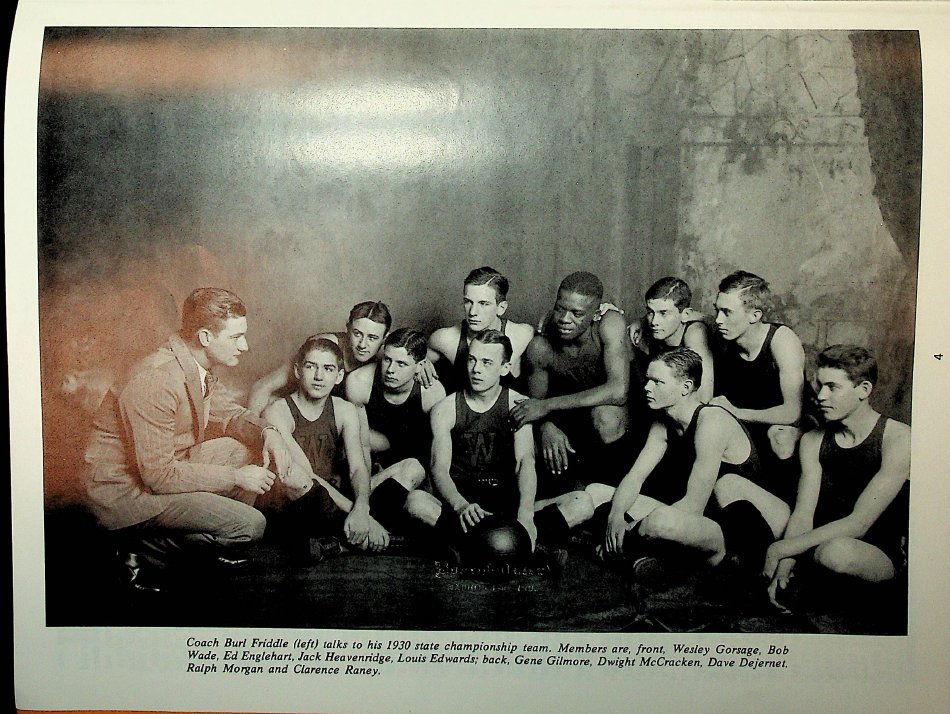

In 1930, the year of Friddle and DeJernett’s State Championship, 760 teams started the tournament. Basketball, undoubtedly, had a strong grip on the state.

Trials and Triumphs

The first black player to play for Coach Friddle and the Washington Hatchets was Harold Bledsoe followed by DeJernett. The two played together in 1929.

By February that season, both players had seemed to win over the hometown fans and the local newspaper. The Washington Democrat predicted that, due to injuries on the team, Bledsoe would see more playing time for the Hatchets when the team traveled to Evansville Central. The paper ran individual pictures of the two and the byline over the pictures read, “IT LOOKS DARK FOR EVANSVILLE.”

The article in the “Basket Bawls” section of the Democrat dated Saturday, February 29, 1929, printed the following:

“When the Hatchets meet Central’s Bears at Evansville tonight, Helms and Englehart will be on the sideline, nursing injuries. But at that, it looks pretty dark for Evansville, for Bledsoe will undoubtly get a call to action in the game and of course, Big Davey Dejernett will be in there at center!!!

Both boys are favorites with the local fans, but ‘Big Dave’ has been playing regularly and gets a big hand for everything he does. This Dave boy has some basketball in him. In fact, he doesn’t realize just how much basketball ability he does have…..……..He has two more years of school and what he does on the hardwood during those years will be plenty of everybody’s business.”

Friddle and the 1928-29 Hatchets made it to the semi-finals of the State Tournament. DeJernett played well enough to make the 1929 State Basketball Tourney First Team selected by the Indianapolis Star.

A Championship Season

The 1929-30 season looked very promising for Friddle and his Hatchets. However, 170 miles northeast of Washington, the Muncie Central Bearcats were also eyeing a state championship run. The Bearcats, coached by Pete Jolly, also had a big-time center, 6-7 Jack Mann who also was black.

The two teams rolled through the regular season and collided in the State Championship game. Washington prevailed, 32-21.

I think about that game a lot. The winner of that game becomes the first black player to win a state title in Indiana High School Basketball history. The coach of that game is the first coach to ever coach a black player on a state title team

If Muncie wins, I’m writing a different story. If Washington loses, Friddle and DeJernett and that community become less relevant to the history of race relations in Indiana and the history of our game.

All the firsts and accolades go to Friddle, DeJernett, and the Washington Hatchets.

Why them?

Then again, why Joe Louis? Why Jessie Owens? Why Jackie Robinson?

Is it destiny? Is it fate? Those are questions that can only be divinely answered. I know that as a 64-year-old native Hoosier, I am proud of what happened in Washington, Indiana so long ago.

To put what DeJernett, Bledsoe, Mann, and other black players at the time were doing into perspective – the first black basketball player at Indiana University and in the whole Big Ten was Bill Garrett in 1948, a full generation after DeJernett was an Indiana state champion.

By the way, Jolly, Mann, and the Muncie team won their state title a year later in 1931 beating Washington in a tournament rematch, 31-23.

Big Celebration, Bigger Target.

Winning the state title made Friddle and DeJernett instant celebrities. Newspapers across the state reported on their victory with the team’s picture and individual photos of Dejernett. One action picture of DeJernett was even printed in China. More people showed up in Washington to welcome the team back from the tourney than the crowds that gathered for President Coolidge and President Hoover on their stops through town.

The success put a bigger target on Big Dave’s back. DeJernett received a threatening letter from 14 KKK members about playing in the 1931 regional finals taking place in Vincennes. DeJernett played in the game and the reigning state champs prevailed 22-19.

DeJernett’s dad watched the game with a gun in his pocket. Dave had 14 points. The Washington press pointed out he scored a point for each signature on the letter.

A Story Kept in Secret

The second floor of the newly renovated Daviess County Museum in downtown Washington is home to a six- paged typed document with the dates Feb 22, 1912 – Aug 8, 1964 hand written at the top of page 1. The dates are the birthdate and day of death for Dave DeJernett. There is no mention of an author.

Volunteer curators at the museum believe the record was written by his mother or another close family member. The document is a big source for this story.

On page one it seems fairly evident that the writer is quoting Burl Friddle:

At the beginning of the 1928 season DeJernett was the outstanding candidate for center on the Washington team. He had no experience, but because of his size I wanted to use him…However, simply because he is an outstanding player, DeJernett has been made the target of more abuse than any basket ball player in the state’s basket ball history.

And this abuse is wholly unmerited. Likewise it is a reflection on the alleged good sportsmanship of numerous Indiana hardwood coaches and sports writers, as well. Washington naturally knows the big boy better than any city in the state and it knows that he is as clean a basket ball player as was ever donned a uniform…

Another section of the document tells of comments from a radio announcer in Indianapolis:

An announcement over WFBM radio station at Indianapolis following DeJernett’s masterly performances during the thrilling Washington-Shortridge game said that the famous center’s sportsmanship as well as his playing ability, was praised by the announcer with commentary remarks as “DeJernett the great, DeJernett the wonderful.” Some of this black majesty’s ancestors somewhere, sometime, must have done something noble, something great. He has the stuff of which heroes are made.” All of which is extraordinarily refreshing and a glowing tribute to DeJernett’s exceptional qualities as a basket ball player. It is a fitting rebuke to those who wont to ostracize him because of his color, and an encouragement to others of his race who are equally efficient. The unusual confidence reposed in him by his white colleagues is remarkable. This is conclusive proof of the high esteem in which DeJernett is held by his fellow players, and a highly profitable asset to the aspirations of the group of which DeJernett is a typical representative.

DeJernett’s fame as a basket ball player is firmly established, and unquestionably meritoriously so. And there will be few, if any to challenge the eulogy he has received as a recompense. Indiana citizens are justly proud of his fine accomplishments in the game. For the Washington Hatchets we have nothing but unmixed congratulation and praise, for without the teams demonstrated impartiality as to color, DeJernett would never have had the opportunity to exhibit his genius.

Obviously the writer had a lot of emotion in sharing things not expressed in public. And yet here we are 90-plus years later, reading information the author thought was important enough to put down on paper. I am grateful for the author’s willingness to share pieces of the story that might never have been revealed.

The document ends with a poem in honor of Dave. Like the rest, the author of the poem is unknown.

“So Long Dave, So Long”

Jumpin’ Dave with kinky hair,

Always tryn’—always square;

Never waitin’ for the gun,

Always workin’—heaps of fun

Always smilin’—full of zest,

Always aim to give your best.